The People of Tolson’s Chapel

(click for text with citations)

The first group of Tolson’s Chapel trustees included Samuel Craig, David Simons, Wilson Middleton, Jacob Turner, and John Francis. David Simons and John Francis were both free men as early as 1860. John Francis was twelve years old in 1860 and already lived apart from his family on a farm outside of Sharpsburg. He would have been only nineteen in 1867 when he was listed as a chapel trustee on the deed. David Simons was twenty-eight years old in 1860 and worked as a Laborer. He and his wife Margaret had two children at the time: Laura, age five, and James, just eight months old. Simons served as the teacher for the Sharpsburg Colored School from 1874 to 1877 and as trustee of the school from 1877 until his death in 1908. Simons was buried in the Tolson’s Chapel cemetery in 1908.

Wilson Middleton was born in Loudoun County, Virginia. Middleton was likely a slave in Virginia, freed by the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. In April 1865, he enlisted in the U.S. Army in Richmond, serving with the 115th Regiment, Company F, of the United States Colored Infantry. Middleton mustered out of service with his regiment in February 1866 in Texas where they were on duty in the District of the Rio Grande. He arrived in Sharpsburg early in 1866 and by October 1867 was listed among the chapel trustees. Middleton lived in Sharpsburg, working as a day laborer, throughout the 1870s and 1880s. He and his wife Moriah (Hammond) had eight children and “occupied a highly respectable position in the community.” Wilson Middleton died in 1891, about sixty-four years old, and was buried in the Tolson’s Chapel cemetery.

Early members of the chapel congregation included both town and farm dwellers. Many were former slaves, including several who were living on the farms of the Antietam battlefield at the time of the battle in September 1862. Jeremiah Cornelius Summers was born a slave in 1849 on the Henry Piper farm near Sharpsburg. At age thirteen, Jerry accompanied the Piper family when they abandoned their home as the Confederate army began to set up their line of defense across the farm’s fields and orchard. Two years later, in April of 1864, Jerry was “enlisted” into the Union army. Only fifteen years old and reportedly much loved by his owner Henry Piper, Summers was permitted to return home as the slave of a Union loyalist. After his emancipation in November 1864, Jerry continued working and living on the Piper farm, employed by Henry’s son Samuel. Henry Piper retired to his stone house in nearby Sharpsburg, where he employed another former Piper slave, Jerry’s brother, Emory Summers. Both Jerry and Emory Summers were active members of Tolson’s Chapel throughout their lives. In 1924, Fred W. Cross, a visitor to the Antietam Battlefield, took several photographs of Jerry Summers at his home located on Bloody Lane on the northern edge of the Piper farm. Cross described Summers as “the last of the slaves of Sharpsburg,” noting:

At Henry Piper’s death Jerry was given the use for life of a small cottage and garden plot facing the northerly stretch of the “Bloody Lane.”

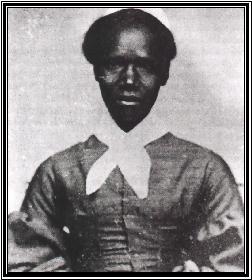

Jeremiah Cornelius Summers, photo taken by Fred W. Cross at Summers’ home on Bloody Lane in 1922 (photo courtesy Doug Bast)

Jeremiah Cornelius Summers died the following year in 1925 at the age of seventy-six; his wife, Susan Keets Summers, followed him in 1942. Emory Summers died in his eighty-third year, in 1941.

Hilary Watson and Christina Watson gravestone in Tolson’s Chapel Cemetery

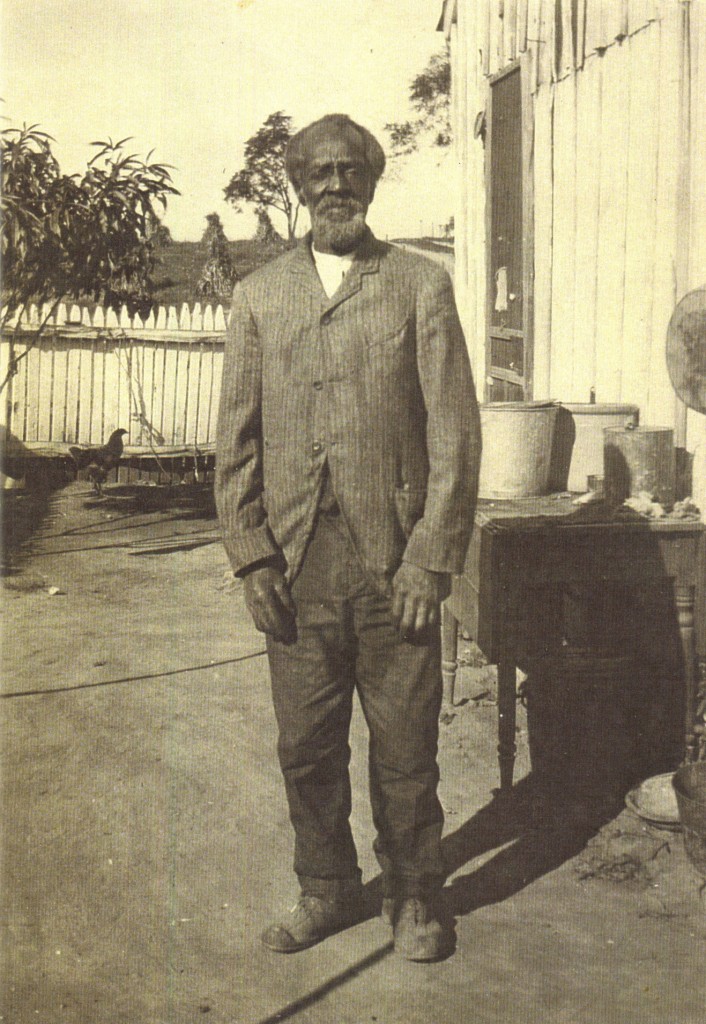

In 1860, John Otto listed two slaves on his 60-acre farm near the Antietam Creek’s Lower Bridge, later known as Burnside’s Bridge, including a twenty-seven year-old man named Hilary Watson. During the 1862 battle Hilary stayed at the Otto house recalling in a later interview: “I didn’t like those shells a-flyin’, and I got on one of the horses and led some of the others and went off across the Potomac to the place of a man who was a friend of my boss. There I stayed all day listenin’ to the cannon.” In May 1864, when Watson was called in the Union draft, Otto paid the $300 fee to release him from military service. Watson continued to work for John Otto following his emancipation in 1864, and by 1872, Hilary and his wife Christina purchased a lot on High Street in Sharpsburg on which they built a log house. Watson served as a trustee of Tolson’s Chapel beginning in 1883 and his wife, “Teany,” was listed in 1881 as one of the managers of a church festival along with Harriet Gray, Emma J. Cook, Mary E. Smith, Harriet Brown, and Louisa Green. Hilary Watson died at the age of eighty-five on September 20, 1917. His wife “Christiana” had preceded him in death on August 25, 1915 at the age of eighty-seven.

Nancy Camel (Campbell) was 40 years old and free in 1860. She was employed as a servant on the William Roulette farm, where 15-year old Robert Simon also worked as a farm hand. Nancy was the former slave of Peter Miller, uncle of William Roulette’s wife, Margaret Ann Roulette. In June 1859, Andrew Miller freed Nancy Campbell. Nancy, who later changed her name to Nancy Camel, appears to have immediately taken employment in the Roulette home where she remained for the rest of her life. She was a member of the Tolson’s Chapel congregation as well as the Manor Church, a Dunker congregation north of Sharpsburg. In 1883, “Mrs. Nancy [Cammell]” inscribed and donated a large bible to Tolson’s Chapel. After her death in 1892, Nancy was laid to rest in the Manor Church cemetery. In her will, she divided her $867 cash estate among Susan Rebecca Roulette, William’s daughter, and the children of both Peter and Andrew Miller, as well as $20 each to the Manor Church and Tolson’s Chapel.