“The Dignity of Free Men.” The Story of Tolson’s Chapel

(click for text with citations)

One of the great ironies of the American Civil War occurred in Maryland with President Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation following the Union “victory” on the Antietam battlefield near Sharpsburg in September 1862. The Emancipation Proclamation freed all slaves in the rebellion states in January 1863. Maryland, however, was a border state, a slave state still within the Union. Maryland slaves had to wait until November 1864, when a new Maryland Constitution set them free. No doubt this irony was not lost on the people enslaved on farms on and near the Antietam battlefield.

Still, emancipation did come to the enslaved African-American people of Maryland. In Washington County, newly freed black families joined their free brethren in establishing communities in rural areas or in sections of established towns. In many cases there was already a core of black families, free before the Civil War, in possession of land or other resources on which to build. For all of these communities, the establishment of a church was an early goal.

Independent African-American churches were largely an outgrowth of emancipation. Although the early Methodist Episcopal Church (today’s United Methodist Church) was vocal in its opposition to slavery the general membership was not prevented from owning slaves. Many black members split from the Methodist church over the issue of slavery around 1794, creating the African Methodist Episcopal church (A.M.E.) in the mid-Atlantic region. Some blacks, however, remained with the Methodist Episcopal Church. Following emancipation, black communities established their own congregations, worshipping separately from their white neighbors. The result was the phenomenal growth of African-American sects of the established denominations such as the Methodist Episcopal and Baptist, as well as the A.M.E. Church.

Independent African-American churches were largely an outgrowth of emancipation. Although the early Methodist Episcopal Church (today’s United Methodist Church) was vocal in its opposition to slavery the general membership was not prevented from owning slaves. Many black members split from the Methodist church over the issue of slavery around 1794, creating the African Methodist Episcopal church (A.M.E.) in the mid-Atlantic region. Some blacks, however, remained with the Methodist Episcopal Church. Following emancipation, black communities established their own congregations, worshipping separately from their white neighbors. The result was the phenomenal growth of African-American sects of the established denominations such as the Methodist Episcopal and Baptist, as well as the A.M.E. Church.

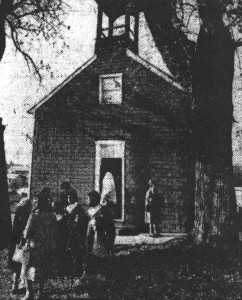

The story of the post-emancipation African-American community in Sharpsburg centers around a tiny log Methodist Episcopal chapel on High Street. A symbol of not just freedom but determination, Tolson’s Chapel became the spiritual and educational center of a vibrant community of black families. While many members of that community had been born free, others were freedmen, born into slavery and freed through manumission, or emancipation in 1864. Their stories are preserved in the little church on the back street of Sharpsburg.

Throughout the week prior to the emancipation of Maryland’s slaves, a meeting of black Methodist Elders and preachers was held in Baltimore to organize the Washington Conference. The timing of this first Annual Meeting in Maryland was not lost on those gathered. Noted the presiding Bishop on the final night of the conference:

Ninety Thousand of your brethren…will lie down tonight…with the manacles of Slavery upon them, but when the midnight hour shall strike, even as the angel came and unloosed Peter, and he arose a free man, so shall their chains fall off, and these thousands shall rise to the dignity of free men.

Following the weeklong meeting the Elders of the Washington Conference assigned local preachers to mission churches throughout the region. Among them, John R. Tolson, a former slave from Virginia, was assigned to the Hagerstown Circuit in 1865 with three churches and 161 members. Sometime in 1865 or early 1866 Tolson established a new mission church to serve the free and newly freed African-Americans living in the still battle-scarred Sharpsburg area.

From as early as 1800, the town of Sharpsburg included a small population of free blacks as well as slaves. Samuel Craig was listed a free man in Sharpsburg on the 1840 census. By 1860 Craig owned real estate in town, eventually acquiring four lots on the north side of High Street. In October 1866, John Tolson’s Sharpsburg congregation laid the cornerstone for their Methodist Episcopal chapel on the southwest corner of Samuel Craig’s Lot 104 on High Street. A local newspaper recorded the chapel’s construction noting:

The African Church, of which the Corner Stone was laid a few weeks ago, is framed, and will be ready for worship about the holidays.

In 1867, Samuel Craig deeded the corner of Lot 104 with the chapel building to the trustees of the Sharpsburg Methodist Episcopal Church. This first group of trustees included Samuel Craig, David Simons, Wilson Middleton, Jacob Turner, and John Francis. Wilson Middleon and John Francis had both been slaves before the Civil War. The chapel was dedicated in October 1867 without Tolson, who was by then assigned to a new circuit in Winchester, Virginia. In 1870, the Rev. John R. Tolson died at the age of thirty, but his Sharpsburg congregation honored him, by ascribing his name to their house of worship.

Members of the Tolson’s Chapel congregation were valued employees and community members. But the 1864 constitution that freed the slaves of Maryland provided little civil recourse for the treatment many blacks received at the hands of white employers, neighbors, and even county governments. The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, more commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, was created by Congress in 1865 to address issues of Reconstruction in the South. The Freedmen’s Bureau operated also in southern Maryland and in the counties around the Federal capital city. But by 1866, the Bureau’s activities expanded to cover all of Maryland, a result of numerous complaints of unfair and abusive treatment of black Marylanders.

Perhaps the greatest impact the Freedmen’s Bureau had in western Maryland was its help in the establishment of freedmen’s schools. Although an 1865 Maryland law required that school taxes collected from black landowners “shall be set aside for the purpose of founding schools for colored children,” this provided precious little in the form of monetary support for black education. Given the small number of black landowners at the time in Washington County, less than 100 in 1870, the school taxes collected there were actually quite small. In February 1867, Washington County School Board minutes recorded, “…the appropriation made in November last [$30] to Colored Schools shall be equally divided between Williamsport and Hagerstown.” And a year later they paid “to the Colored Schools of the County – the sum of $25 a piece.” Based on this, in 1868, the Board reported to the Freedmen’s Bureau that it had “paid what the law allows for these schools.” According to the Freedmen Bureau’s local agent in Harpers Ferry, it was the only county in Maryland to have done so.

The Tolson’s Chapel trustees and congregation knew that education, so long denied African-Americans both slave and free, was key to economic growth. Apparently ignored by the county school board they offered their church building early in 1868 to house a Freedmen’s Bureau school. The Bureau was to provide a teacher, but it was the community that would pay his wage, board, and housing. On March 28, 1868 after a visit to Sharpsburg, Capt. J.C. Brubaker, agent of the Freedmen Bureau’s Harpers Ferry region, wrote a letter to Rev. John Kimball, Superintendent of Education for the Bureau in Washington, saying:

The colored people are very anxious to have the school opened and from the spirit manifested I am assured that they will fulfill their part of the contract.

The school’s teacher, Ezra A. Johnson of Philadelphia, reported his arrival in Sharpsburg in April 1868 noting, “I have opened a day school, night school, and Sabbath school and will this week organize the Vanguard of Freedom.” Johnson christened the school the “American Union” school. Initial attendance included eighteen students, only six of whom had been free before the war. On the chapel wall they painted a blackboard of “slating” or “liquid slate” (made with lamp black and shellack) on which write their lessons. In 1869, attendance rose to twenty-five students with a new teacher, John J. Carter, supplied by the Presbyterian Committee of Home Missions (PCHM). Carter, a Lincoln University graduate, reported “They learn very fast.” The PCHM paid the Tolson’s Chapel trustees ten dollars per month for the use of the church building as a school. The American Union School in Tolson’s Chapel was one of seven schools initially sponsored by the Freedmen’s Bureau in Washington County and is the only one still standing today.

Congress discontinued the Freedmen’s Bureau school program in 1870 and it fell to the county to provide educational opportunity to its black residents. In 1874 the Washington County school commissioners confirmed David Simons as the teacher at County Colored School No. 4 in Sharpsburg, still located in Tolson’s Chapel. Simons served there as teacher until 1877 when George Smith took his place. James F. Simons, son of David, assumed the role of teacher in 1879 and remained for more than thirty years. Historian J. Thomas Scharf recorded the 1881 report for County Colored School No. 4 in Sharpsburg, with 22 pupils under the tutelage of James F. Simons.

In August 1876 the Board appropriated “the following sums as rent for the school houses,” including $15 for Colored School No. 4 in Sharpsburg. Rent paid for schoolhouses was not recorded in the minutes of the School Board again until 1899 when $20 was paid to “D.B. Samons, Treasurer” at the Sharpsburg school. That same year, in 1899, Hilary and Teenie Watson sold to the county Board of School Commissioners part of their Lot 101 on the corner of High and Church Streets. There the county built a frame schoolhouse called the Sharpsburg Colored School at a cost of $682, ending thirty-one years of operation in Tolson’s Chapel.

Throughout the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth century Tolson’s Chapel, in addition to hosting a school, was the center of an active community, holding services and Sunday school, fairs, festivals, and Bush Meetings. The “Hagerstown & Sharpsburg Circuit” in 1871 was served by Philip Scott. At that time the Sharpsburg “station” listed 25 members, 2 deaths, 10 child baptisms, 9 officers & teachers, and 55 [Sunday school] scholars. Preacher Daniel Aquilla, who served at Sharpsburg in 1870, was assigned to the “Williamsport & Sharpsburg Circuit” in 1872. That year, Sharpsburg listed only 12 members, with 1 death, 1 adult baptism, 12 child baptisms, 4 officers & teachers, 20 scholars, and 20 volumes in the library. Jacob M. Gross was stationed at Sharpsburg in 1873, when the Committee on Missions recommended $100 be given to Sharpsburg, a relatively large sum compared to others that were mostly $25-50. In 1874, the Sharpsburg station had 37 members, 19 probationers, 3 deaths, 4 child baptisms, 5 officers & teachers, and 45 scholars.

Chapel trustees purchased at least 16 Sunday school hymnals in 1875, inscribed in the front cover “Sharpsburg T C [Tolson’s Chapel] 1875.” Also a set of Bibles printed in 1880 were purchased from “F. Markell, Books and Stationery, Frederick City, Md.,” several inscribed with warnings: “Children after reading your lesson return it to the Sup. [Superintendent]” or “Never take this Bible from School.” And after 1891, Wilmore’s New Analytical Reference Bible was purchased for use during Sunday services; the same Bible was left open on the lectern when the chapel doors were closed 100 years later. The local newspapers reported a bush meeting being held by the “colored people of Sharpsburg” in David Otto’s woods on September 29, 1888 with Rev. John H. Bailey officiating. On November 20, 1891 a revival was held in the “AME” church in Sharpsburg, also reported by the local newspaper, although technically Tolson’s Chapel was not affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) sect.

In June 1883, chapel trustees Hilary Watson, David B. Simons (spelled Samons in the deed), and William H. Gray purchased the remaining west half of Lot 104 bordering the church “in trust for the said Methodist Episcopal Church called Tolson’s Chapel.” This was the cemetery lot, and although there are a number of unmarked graves in the cemetery, none of the marked graves pre-date this 1883 conveyance. Perhaps the earliest stone was for “Mehaley Thomas, age 100y[ears],” but it did not include a date of death. However, Mahala Thomas’ death at the age of 104 was reported in the September 29, 1888 issue of the Antietam Wavelet. The M.E. Washington Conference minutes recorded among the Sharpsburg statistics two deaths in the church in 1871, one death in 1872, and three deaths in 1874, so it is likely that burials began as early as 1871.

Beginning in the 1890s and through the 1920s, the Tolson’s Chapel cemetery was relatively active with burials. In 1891, Wilson Middleton died, “an aged and highly respected colored man and an ex-union soldier,” noted the local newspaper. In 1893, Minnie May Beeler, age 9 months and daughter of George W. and Julia Beeler, was buried. Carlina (Summers) Jackson, probably daughter of Jeremiah and Susan Summers, died November 24, 1893. And in 1895, forty-five year-old Harriet A. Robinson, adopted daughter of Hilary and Teenie Watson, passed away. Several of Sharpsburg’s former slaves died in the first decades of the twentieth century, including Hilary Watson (1917) and Jerry Summers (1925). David B. Simons died in 1908 at age seventy-six, and his son, Rev. James F. Simons (school teacher and ordained minister) died in 1911. In 1955, Mary E. (Lizzie) King devised in her will “One Hundred ($100.00) Dollars, for the express purpose of erecting a fence around the grave yard adjoining said Tolson Methodist Church.” The most recent marked grave is that of Frances M. (King) Monroe, wife of Clarence Monroe. Mrs. Monroe died in 1995 and with Virginia Cook, who died in 1996 (no marker), was the last of the Tolson’s Chapel congregation that stayed in Sharpsburg. In all, the cemetery list appears to represent from 12 to 15 families with many inter-marriages.

Sharpsburg was home to approximately 85 African-Americans by the 1930s, including farm laborers, shopkeepers, housekeepers, and several skilled house carpenters. However, employment opportunities for the young led many to the city of Hagerstown, a scenario repeated in the rural towns throughout Washington County. As the elderly who remained passed away, the congregation at Tolson’s Chapel dwindled.

In 1976, one hundred and ten years after the chapel’s construction, a local newspaper announced, “Sunday’s Rally Day services at Tolson’s Chapel in Sharpsburg drew a crowd of 30 – ten times the size of the little congregation’s membership.” As Virginia Cook, the chapel’s matriarch, led the reporter through the sanctuary, she noted:

Warmed by a cast-iron, pot-bellied stove, its large, bare light bulbs cast a warm glow around the room. And with its old wooden floors, handmade pulpit and pump organ still intact, the chapel looks just the way it did when I was a little girl.

Citing only three black families still living in Sharpsburg, Miss Cook noted the Rally Day donations would “keep us going” another year. Among the last of Tolson’s Chapel’s then surviving members, Virginia Cook recorded some of the chapel’s history in an undated letter, recalling:

The conference furnished us a pastor and where we fell short with our money, Mr. Calan would go around to the farmers for chickens and milk and the older ones fixed the chickens and made Home made ice cream. We made good off them. People seemed to buy and help out.

To this day, older citizens of Sharpsburg recall with fond memory the chicken and ice cream produced for the Tolson’s Chapel festivals. The Rev. Ralph Monroe took over the care of the chapel and grounds as the last active members passed away, including his mother Frances Monroe and Virginia Cook. Ralph Monroe grew up a member of the Tolson’s congregation but left Sharpsburg during his service as a Methodist minister in the region. In 1998, the local conference of the United Methodist Church decided to close the church. With the Bible still open on the pulpit and the list of the last Sunday’s hymns still posted on the Hymn Board, the door was locked.

Now 143 years old, Tolson’s Chapel still stands on East High Street in Sharpsburg. The story of Tolson’s Chapel and the lives of the men and women associated with it breathes life into this artifact of American history. How much more personal does the African-American struggle for freedom become knowing Jerry and Hilary, slaves on Antietam battlefield and active members of the Tolson’s Chapel congregation? And how much more inspiring is the story of education after emancipation when standing in Tolson’s Chapel envisioning the eighteen students in 1868, twelve of whom had been slaves four years earlier?

Tolson’s Chapel is now under the care of the Friends of Tolson’s Chapel, dedicated to the restoration, preservation, and interpretation of this very special historic building. The Friends of Tolson’s Chapel (FOTC) was established as a 501(c)(3) non-profit association in 2006, after working as a sub-committee in the Save Historic Antietam Foundation (SHAF) for four years. SHAF initially took ownership of the chapel and grounds in 2002 in order to initiate emergency stabilization. Using grant funds from the Maryland Historical Trust, Preservation Maryland, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the National Park Service, the building’s log structure and stone foundation was stabilized and repaired. In 2008 ownership of Tolson’s Chapel was transferred to the FOTC. The Board made the decision to restore the church to its nineteenth century appearance, based on architectural and documentary evidence. Since that time restoration work has continued with repair of the windows, restoration of the board and batten siding and wood shingle roof, reconstruction of the bell cupola, repair of the interior plaster, and simulated whitewash on both the interior and exterior walls. Interpretive projects include a furnishing study and development of the educational website. Other projects include restoration of the liquid slate blackboards, exterior shutters, and central chimney, and a condition assessment of the cemetery and gravestone conservation.